Modernizing New York Commuter Rail:

A Brief Summary

The New York region is finally beginning to tackle one of the most congested links in its entire transportation network—the tracks under the Hudson River between New York Penn Station and New Jersey—via the Gateway Program. The centerpiece of this program, the $16 billion Hudson Tunnel Project, was recently funded by the federal government, and will double rail capacity under the river from two tracks to four.

On one hand, this capacity boost is absolutely vital for both the regional and national economy, for the ongoing fight against climate change, and for the everyday lives of millions of people in the greater New York area. However, this new infrastructure simply cannot live up to its potential without modernizing the region’s 9-to-5-oriented rail service. Transit in New York, as elsewhere, must meet the demands of 21st-century travel patterns. We increasingly live in a post-peak world: even in 2019, fewer commuters arrived in Manhattan between 8 and 9 am than had been in 1960, even though the total number of commuters rose. With so much money at stake, it is imperative to make sure that this $16 billion investment serves more than just a shrinking commuter market. In short, New York needs to reform commuter rail.

These reforms center around two concepts. In the short term, the most important thing is to raise the frequency of off-peak service, scheduling trains to come more frequently at all times of the day. Subsequently, it is also crucial to implement through-running across Penn Station. This means that trains should continue through Manhattan after stopping at Penn Station —for example, running from Elizabeth, NJ to Stamford, CT—rather than terminate there as they do today. These two changes will anchor a series of reforms that would make commuter rail useful for many other forms of travel, many of which will be discussed in an upcoming longform report from the Effective Transit Alliance.

The Gateway Program currently includes two additional unfunded items: the $17 billion Penn Expansion project, which would condemn an entire Manhattan block to add new tracks to the station, and the $7 billion Penn Reconstruction project, which would redesign the existing station to improve passenger experience and passenger circulation. Penn Reconstruction is a useful project, and the state and federal governments should fund it either in its entirety or in part. Penn Expansion, in contrast, is a massively expensive, majorly destructive boondoggle which is in no way necessary to improve capacity at the station. It should be canceled and replaced by through-running, as recently advocated by none other than former New York City Transit head Andy Byford.

Who Rides Where?: Changing the Commuter Rail Paradigm

The current operating paradigm of American commuter rail is that nearly all riders are city center commuters, while most other trips are made by car. This view is stuck in the 1950s, when there was more regular commuting to Manhattan than there is today. This is particularly notable in the times that people travel. In 1960, 25% of people entering Manhattan south of 60th Street on weekdays did so between 8 and 9 in the morning. In 2019, in contrast, only 16% did. The truth is, people will ride transit—including commuter trains—for many different types of trips if service is provided. Commuter rail must switch to a paradigm in which it serves all types of trips, one in which commuters working in Manhattan may be the largest group of users, but not the only one.

The reforms we propose will directly benefit people commuting from the suburbs to Manhattan. Higher frequencies and through-running would not only mean more service for commuters, but would make train travel more reliable. It would serve, for instance, to soothe the anger of LIRR riders at the opening of East Side Access to Grand Central, and the subsequent loss of frequency to Penn Station to serve Grand Central.

Ultimately, however, these reforms will benefit other groups of riders even more:

Urban trips, which currently face a choice between hourly but fast commuter trains or buses and subways that are far slower, but come every 10–12 minutes.

Commutes to job centers on the opposite side of Manhattan, such as from New Jersey to Flushing, White Plains, and Stamford, or from New York and Connecticut to Newark and a host of other New Jersey job centers.

Airport trips, from New Jersey to JFK or from east-of-Hudson suburbs to Newark Airport.

Student travel between such campuses as Yale, Princeton, Rutgers, Stony Brook, and the many universities of New York City.

Social trips to suburbs and neighborhoods outside Manhattan, such as Flushing, Central Jersey, and Harlem, or historic sites like Sleepy Hollow.

Leisure trips, such as trips from the Bronx and Westchester to the beaches of the Jersey Shore, or trips to sporting events. In fact, there used to be limited through-running from the New Haven Line to the Meadowlands for football games.

Collectively, these groups are large. Here is a map of all cross-regional commutes:

Much of the impetus for this modernization comes from the lessons of other rail systems. While the New York City Subway is not as frequent as would be ideal (see our Six-Minute Service report), trains still arrive once every 10–12 minutes in the off peak. The subway also demonstrates the operational efficiency and rider benefits of through running. F trains, for example, run all the way from Queen through Manhattan to Brooklyn (and vice versa), and while most subway riders get off in Manhattan, a significant portion also stay on for longer trips.

The most modern commuter rail systems in the world today—including places like Tokyo, Osaka, London, Paris, Berlin, Madrid, and Milan—both run very frequent off-peak service and use through-running to maximize their effectiveness. If New York matched that service level, urban stations as far out as Fordham, Flushing, and Newark-Broad Street would see a train every 5–10 minutes or even less, and suburban stations such as Mineola, Rye, and Perth Amboy would have a train every 15–20. This would pay dividends in ridership: each of the aforementioned international networks gets far more usage than the traditional American commuter rail system. Paris’s five-line RER, for example, has four times the ridership of New York’s commuter rail system.

Implementation

New York’s commuter rail operators should sharply increase off-peak frequency immediately. As we explain in the long report, the additional operating costs of even a large increase in off-peak service are very low, but the ridership impact is large.

Then, the region can implement Penn Station through-running in phases. The agencies that operate trains at Penn Station would have to coordinate but not merge. While London’s through-running is done under one roof, Paris and Milan coordinate multiple agencies, and Tokyo even coordinates private railroads, to offer seamless service across their regions.

Through-Running Phase 1

For Phase 1, New York should run trains through Penn Station between Metro-North’s New Haven Line and New Jersey Transit is Northeast Corridor Line:

Unlike other cities such London and Paris, which had to build tunnels to operate through service, New York’s Penn Station is already largely configured for it, meaning service can begin with very little capital expenditure.

The only section of this route needing major work is between New Rochelle and Penn Station, which currently lacks infill stations and is not served by commuter rail. Thankfully, this project is already underway as Penn Station Access, an ongoing, $2.87 billion project that will add four stations and enable Metro-North’s New Haven Line trains to provide service to Penn Station. The project is scheduled to open in 2027, and when it does, service should immediately begin running through to New Jersey. There is simply no good reason not to—connections to the New Jersey side of the Northeast Corridor, including the North Jersey Coast Line, require almost no new infrastructure—and the benefits to both operators and riders are large.

Through-Running Phase 2

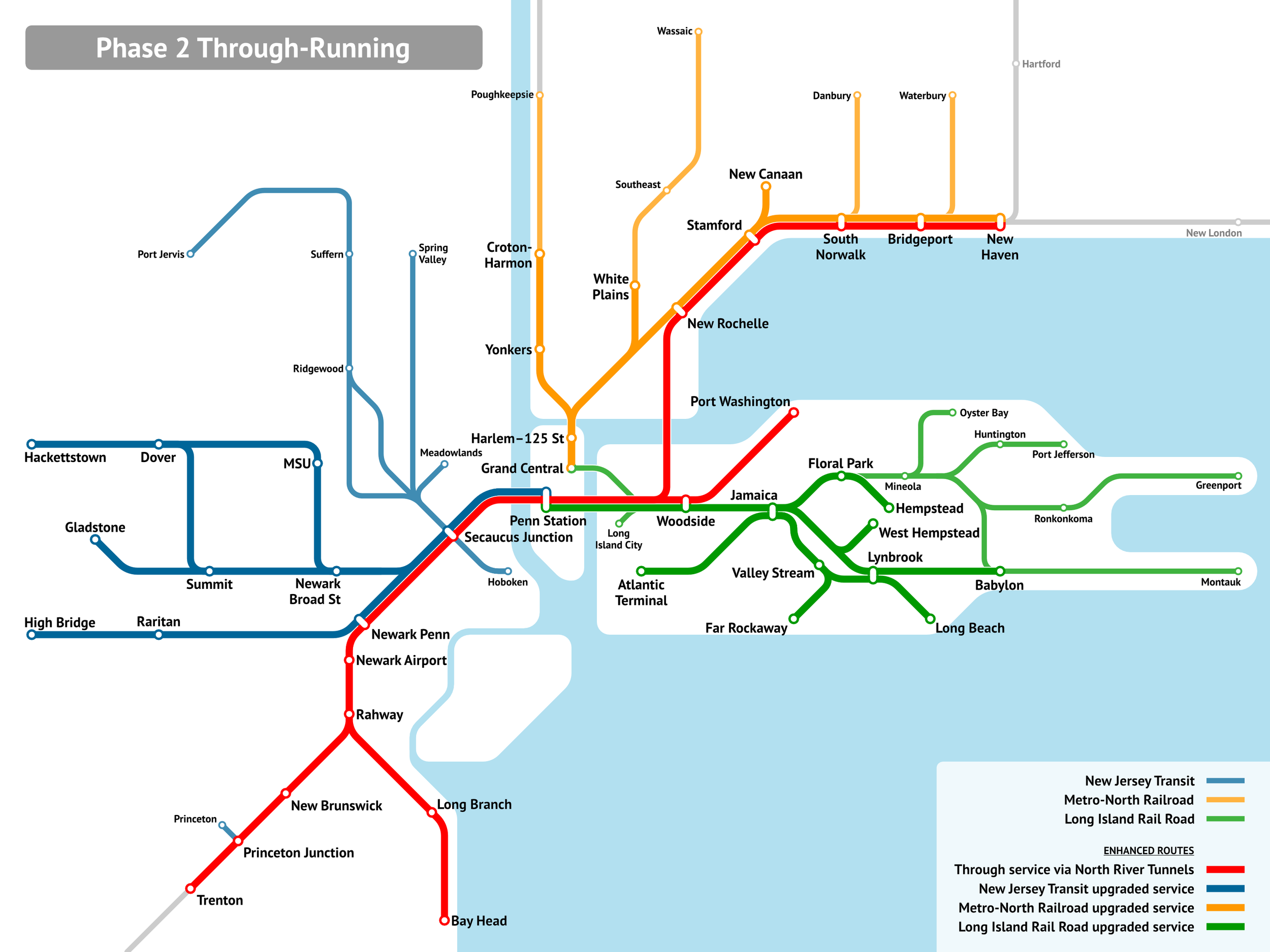

The capacity of phase 1 will be limited, as right now, only the two current tracks under the Hudson between New York and New Jersey exist. Once the Hudson Tunnel Project and a few surface tie-ins (such as the plan to grade-separate the junction to the Raritan Valley Line, Hunter Flyover, for $300 million in 2022 prices) are completed in the mid-2030s, however, more lines can begin running through (phase 2).

Nearly all of the required work is in New Jersey, and much of it is outlined in our New Jersey capital report. In particular, high platforms should be constructed at every station, as level boarding is a cornerstone of universal design for not just disabled passengers but also those with strollers or luggage.

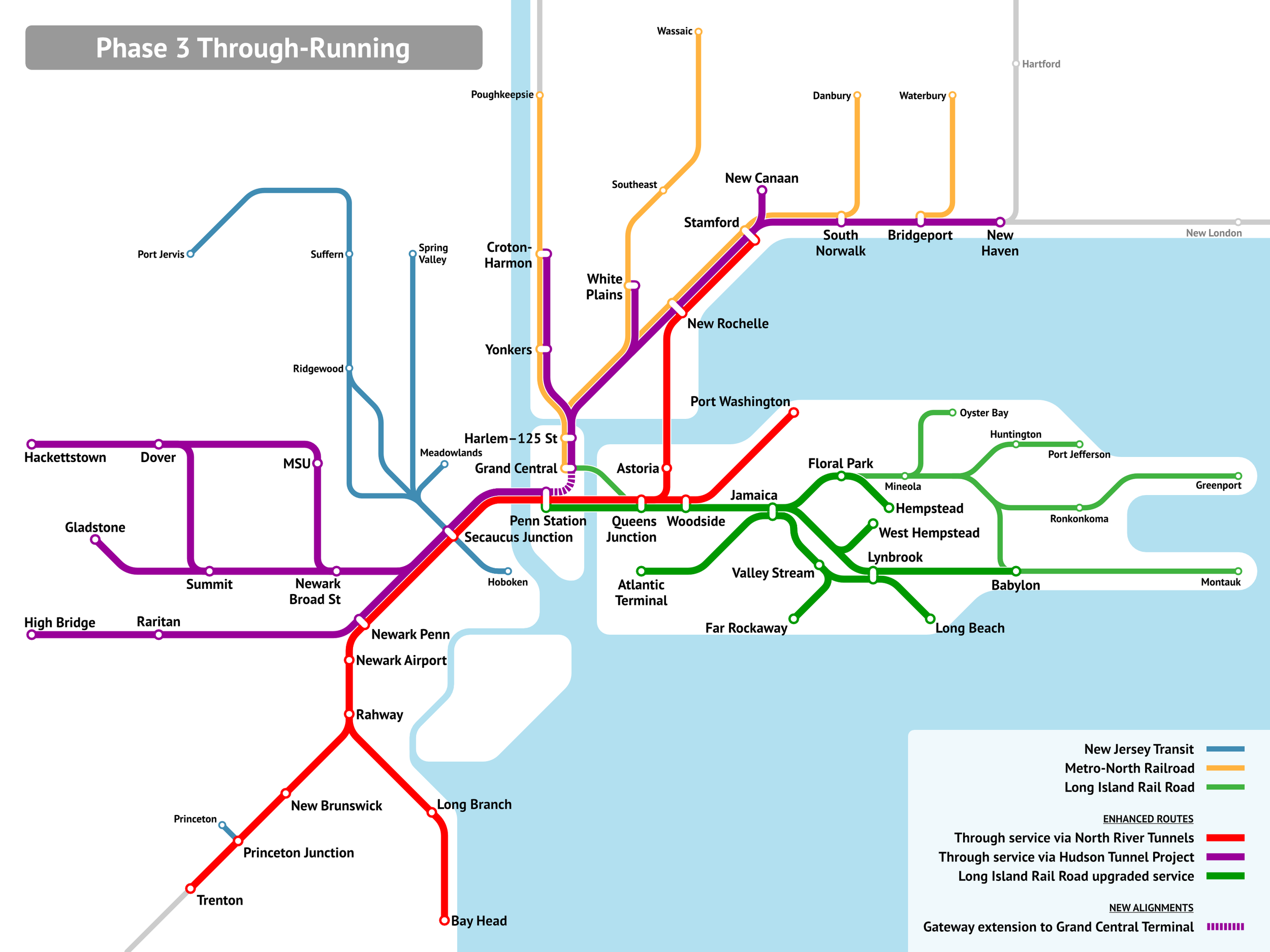

Through-Running Phase 3

Finally, the new Hudson tunnel should be extended across Manhattan to Grand Central to facilitate through-running between Metro-North Railroad and New Jersey (phase 3). This connection would allow Metro-North trains serving Grand Central to continue to Penn Station and then onto New Jersey as New Jersey Transit trains, and vice versa. While this connection would be a major undertaking, it could take much of its funding from the billions of dollars freed from canceling the unnecessary Penn Expansion project. It would create a plethora of though-running opportunities, not only enabling more trains to operate through Manhattan on regional trips, but also allow these trains to serve both the East and West Sides. To get the most out of this connection, it will also be crucial to complete electrification on the outer portions of lines and equip all stations with high platforms to permit level boarding onto all trains.

With Penn Station and Grand Central linked, all New Jersey lines connected to Penn Station should run through to east-of-Hudson suburbs. At the end of the day, however, there will still be more trains on the LIRR and Metro-North, meaning some lines will need to continue to terminate in Manhattan as they do today. A future study on which New York and New Jersey lines are suitable to be paired for through-running is warranted closer to the opening of the physical infrastructure.

You can help

You can advocate for a revamped network that delivers superior service.

Write or call your elected officials, especially the Governors of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, in support of through-running options.

Speak at MTA, Port Authority, and New Jersey Transit board meetings.

Write op-eds and letters to the editor about the advantages of through-running.

Testify at state legislative hearings.

Comment during the Penn Expansion environmental review process in favor of serious consideration of through-running.

Volunteer with organizations that are working to support through-running, including the Effective Transit Alliance (ETA), and the Tri-State Transportation Campaign.