Deinterlining: Simpler Service, Fewer Delays

New York’s subway system is connected by a delicate system of interlining.

Credit: ETA, William Meehan

A House of Cards

Every New York subway rider knows the frustration of train stops and delays. One minute, you are speeding along; the next, you slow to a crawl and stop, for no obvious reason. Even worse, at times every train is running at a snail's pace, all due to an incident that happened miles away, on a completely different line. Obviously, no transit agency can completely prevent unexpected mishaps. They can, however, structure their services to prevent a single incident from spreading delays across the entire system, cascading for hours on end.

The New York City Subway is famously complicated. Many lines are three or four tracks; trains can run local or express; and, crucially, different services often branch and merge with each other. It is this complexity that not only creates the potential for delays, but allows those delays to spread far and wide.

Most well-designed transit networks use branches to fill a central trunk, if branched at all. For example, the A train has branches running to both Far Rockaway and Lefferts Blvd, which allows higher frequency at busier stations in Brooklyn and Manhattan. The same is true of D and N trains, which have separate branches toward Coney Island, but share tracks running express on 4 Av. This type of branching is relatively easy to schedule, as trains can be made to arrive at their merge point at staggered times so that they fit into a neatly spaced pattern in the middle. In this way, trains don't conflict with one another, and they provide more service to denser areas.

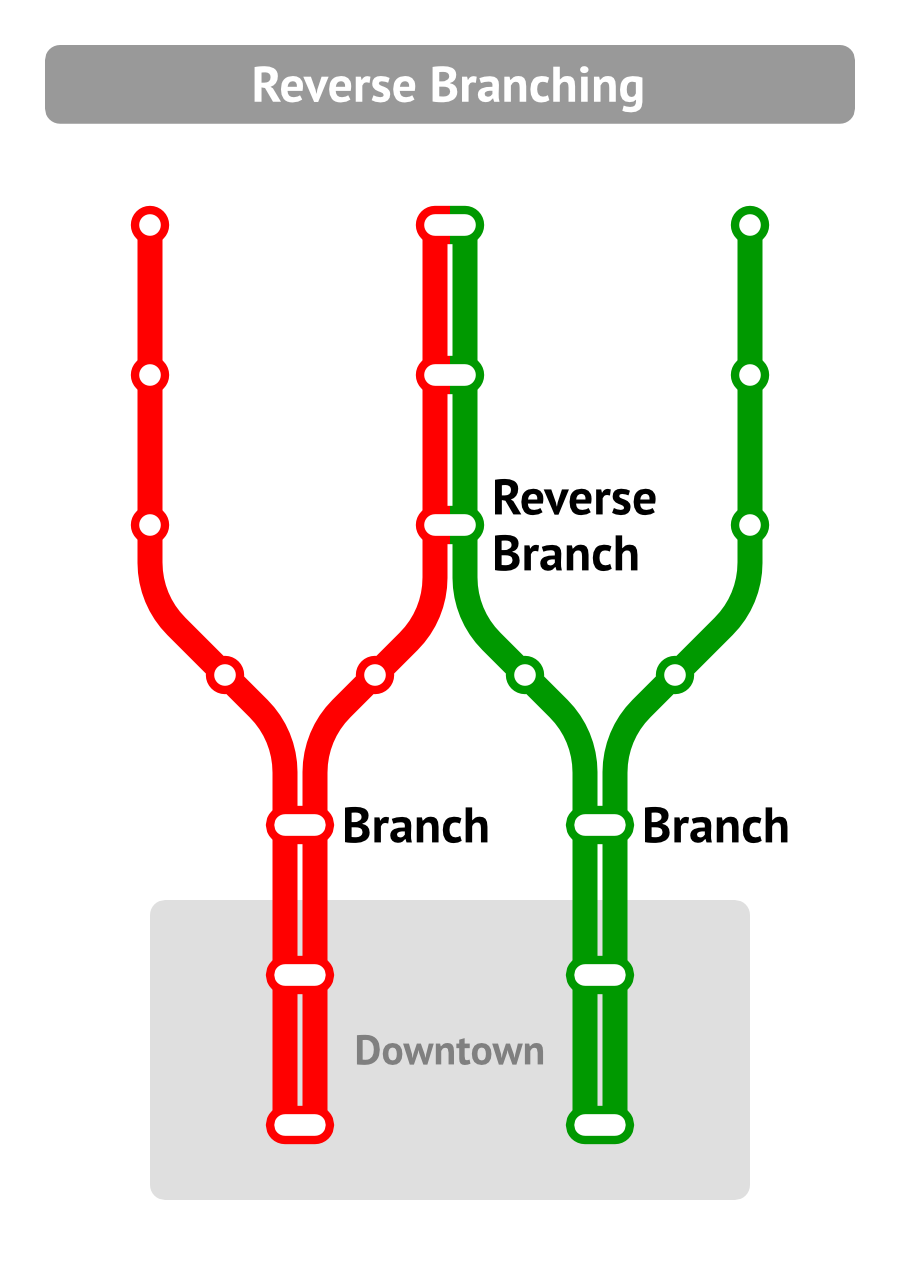

Reverse branching makes scheduling transit systems incredibly complex and allows delays to propagate.

Credit: ETA, Kara Fischer.

The subway, however, also has many reverse branches, where services that have already branched out from one central trunk line join with a branch of another. A prominent example are the 7 Av (2/3) and Lexington Av (4/5) Expresses: these lines branch in the outer boroughs, but the 2 and 5 trains, which run separately in Manhattan, merge onto the same tracks along White Plains Rd in the Bronx and Nostrand Av in Brooklyn. Reverse branches are incredibly difficult to schedule: ensuring that trains always come to interlockings at different times quickly becomes a very difficult, and often impossible, problem to solve. Perhaps worse, when delays mess up this delicate balance, they can cause cascading delays across lines that would otherwise be unaffected.

There is one simple solution to this scheduling and delay-inducing headache: eliminating reverse branches through a process called deinterlining. Deinterlining simplifies the subway’s complex and delicate arrangement, creating a more robust, reliable network. This is why, as the broader transit advocacy has noted for years (e.g., Alon Levy, vanshnookenraggen, Uday Schultz, NYTIP, Joint Transit Association, Mystic Transit), deinterlining is a crucial step in enabling better service on the subway.

Fortunately, the MTA eliminated one reverse branch that was a major source of delays this morning, December 8th, 2025: the F/M swap. They are also planning to eliminate another by addressing the bottleneck at Nostrand Junction as part of the MTA’s 2025–2029 Capital Plan. ETA applauds the MTA for working to simplify its system to make it faster and more reliable. We encourage the agency to go further and also consider deinterlining DeKalb Interlocking to greatly reduce the cost and complexity of the planned 6 Av CBTC installation.

Why deinterline?

The biggest frustration of many transit riders is waiting, whether for the train to arrive at the platform or for it to get moving again if it stops in the tunnel. The worst waits are unexpected ones, when the train is suddenly stuck behind another one or delayed because of switch problems. Interlining introduces new merge points and switch movements and therefore more unpredictable waits.

Interlining makes it far more difficult for the MTA to schedule its services. Two trains cannot occupy the same physical tracks at the same time, so each one must be scheduled to arrive at each station with enough time to alight and board passengers and continue onwards. This is simple for two services that share just one track segment. During peak-hour service, however, today's interlined network requires either tight, often unrealistically short gaps between merging trains, or worse, forces merging conflicts. In other words, interlining not only creates built-in delays, but leaves the schedule of the entire connected subway network liable to collapse from even small delays. For example, a delay on the R in Queens could cascade to the N in Midtown, then to the D train in Brooklyn, which could affect the B in Manhattan, and so on. The result is that a disruption at one location can cascade across the whole system.

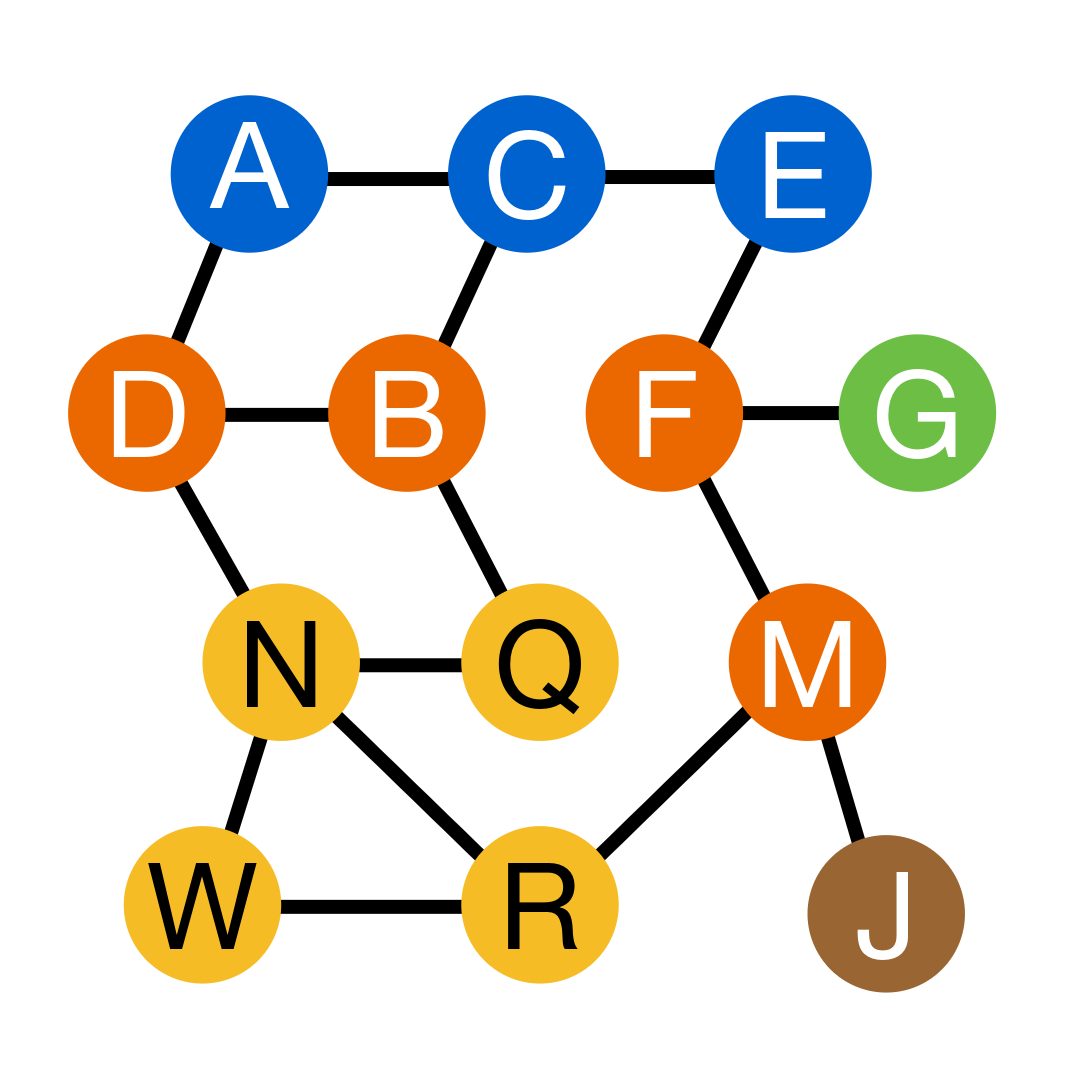

Many of New York’s subway lines are interconnected through delicate acts of interlining, allowing delays to spread.

This graph shows all B Division services that share tracks with at least one other service. Services that share tracks after the F/M swap are connected by a line.

Credit: ETA, William Meehan

To mitigate potential systemwide delays, the MTA limits peak frequency below what is theoretically possible on each line. Even in normal operations, many parts of the system that serve densely populated areas are left with frequency that is poor and uneven due to the compromises needed to make the present heavily intertwined service pattern work.

Deinterlining has several clear benefits:

Improved reliability: Problems with one service are less likely to cascade into problems with other services.

Improved speed: There are fewer delays as one train waits for another and fewer uses of slow switches. Higher reliability allows for reduced schedule padding.

Higher capacity: The limiting factor to train throughput is reliability and regularity, as the minimum headway between trains needs to be scheduled with some slack to allow for delays and slower switches. With fewer delays, the maximum capacity is higher.

Deinterlining is not a new idea: the MTA has discussed it for years. The reason it hasn’t happened—besides sheer institutional inertia—is that reverse branching offers more one-seat rides. Interlining gives riders along certain branches the choice to take trains between multiple trunks without needing to transfer. For instance, today, passengers along Nostrand Av can take a single ride to either the East or West Sides of Manhattan on the 5 or 2 trains, respectively.

While this is an advantage of the current system to some riders, the benefits of deinterlining greatly outweigh the drawbacks. Right now, riders must wait longer for the particular train heading to their destination, and overall service frequency is limited by merge points and scheduling. While deinterlined service will require some riders to make a transfer, the higher frequency and reduced delays of a deinterlined system mean that the vast majority of trips will actually be shorter, even with a transfer. What's more, this service simplification will make it so delays can't spread, making massive meltdowns far less likely.

That said, due to the way that public feedback biases towards the status quo—and because the benefits of deinterlining are not always readily apparent to the lay audience—the MTA has been wary of pushing these reforms in the past. The reality, however, is that most riders already transfer, and deinterlining will make the vast majority of subway rides faster and more reliable.

Opportunity and Risk: the Need for More Service

Deinterlining will enable the subway to run better service. This will especially be true during rush hours, when the current system of complicated merges limits the number of trains that can run. To succeed with the public, however, deinterlining must be linked with an increase in service at all times to ensure that new transfers are offset by reduced wait times. The trust needed for the public to accept changes to their commutes—both for relatively low-impact changes today and potentially more aggressive service streamlining in the future—will be neither kept nor earned.

Peak frequency gains are the most exciting to talk about, especially as they are most clearly what is enabled by deinterlining, but off-peak frequency must also be boosted, because riders remember the worst transfers, even if it has less of an effect on merges. Put simply, riders remember their worst transfers, not their best ones. Riders today often prefer one-seat rides not so much because they involve less walking, but because of the risk that infrequent or delayed service will make their whole trip take far longer.

At the end of the day, one of the major benefits of deinterlining is that it reduces the possibility of delays. Riders will accept additional transfers only if their justified concerns over long waits and significant delays are addressed. For deinterlining to be successful, the MTA must prioritize these lower risks and the higher system reliability. The most effective way to do this is through increased service.

The F/M swap

This morning, December 8th, 2025, the MTA permanently switched the tunnels that the F and M trains use between Queens and Manhattan on weekdays. The F train will instead serve 5 Av/53 St, Lexington Av/53 St, Court Sq, and Queens Plaza together with the E train, and the M train will instead serve 57 St, Lexington Av/63 St, Roosevelt Island, and Queensbridge. On nights and weekends when the M doesn’t run to Queens, the F train will continue to use 63 St.

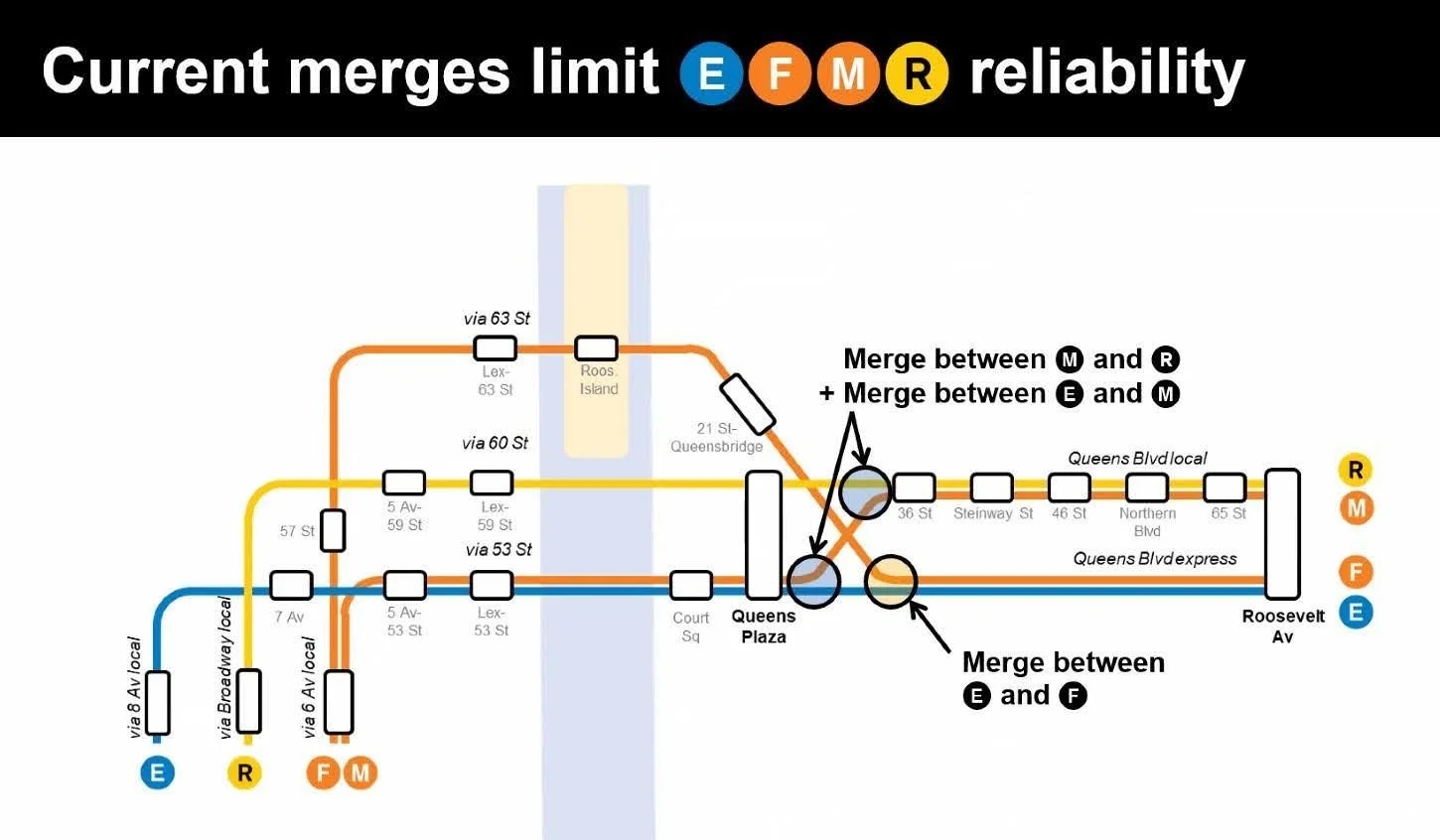

This change will reduce the number of merges between the E/F/M/R in Long Island City from 3 to 1. The current set of merges around Queens Plaza delay a staggering 15–20% of rush-hour E/M/R trains. Instead, the E will now share tracks with 2 other services (the C and F) instead of 3, and the M will now share tracks with 3 other services (the F, J/Z, and R) instead of 4. The F/M swap will isolate the local and express tracks of the Queens Blvd Line, so delays can no longer propagate between the E/F and M/R trains.

Credit: MTA, via Roosevelt Islander

The value of deinterlining was proven by a recent natural experiment. Two years ago, the 63 St tunnel was closed for track replacement, eliminating these delay-causing merges. The MTA used the closure as an opportunity to collect data on how these changes might affect train service. During the work, riders saw faster and more reliable trips, including at peak commute times. Based on this data, the MTA expects that for every rider who sees a longer commute, 2.5 riders will have shorter trips, saving riders a cumulative 2 months of time during rush hour every day [1]. Only 2% of riders will see their trips slowed by more than 4 minutes. And all riders will see far more reliable service.

Crucially, the MTA has committed to improving peak M train frequency on the 63 St line from every 6-7 minutes to every 6 minutes, 1 minute longer than average waits for the current F (every 4 min). This is the key to successful deinterlining, ensuring that 98% of riders see faster or the same commutes. With the increased frequency, frequent and reliable transfers diminish the value of one-seat rides. It would be better yet if M frequencies could be raised further; however, turnback capacity at Forest Hills and merge delays at Myrtle Av with the J/Z limit how many more M trains can be run.

The schedule released by the MTA today, however, only shows a small increase in service over the course of the day. There will be 9 tph both before and after the swap, with only 6 out of 18 morning rush-hour M trains having the promised 6-minute headways or better. We hope that the MTA will continue to improve M service in upcoming schedule updates, at least up to the promised 6-minute headways, to ensure that as many people as possible see a positive impact from this change.

The F/M swap is a perfect place to start deinterlining, as it will actually provide many one-seat rides and significantly reduce crowding. Most demand from Queens Blvd is towards the 53 St line and its connection to both the 6 and the core of Midtown. The F/M swap will increase service from 24 tph (trains per hour) to 30 tph on 53 St, significantly reducing the extreme crowding, especially at Lexington Av–53 St. Riders at that station can now take an E or F express train every two minutes, instead of what most currently do: wait four minutes for an E while avoiding a local M. Better still, most F riders actually originate east of Forest Hills and those commuters prefer 53 St. This change will give them a one-seat ride on the F instead of forcing a transfer to the more crowded E.

These are precisely the benefits that we expect from deinterlining, and it’s great to see NYCT President Demetrius Crichlow touting them. It’s also important to note that, because these trains travel across the entire city, these benefits affect the entire service, not just where the deinterlining occurs. That means riders many miles away, who may rarely if ever go to or through Roosevelt Island or Long Island City, also benefit. Indeed, half of the subway system will become incrementally more reliable overnight with this change.

The one unfortunate drawback to the F/M swap isn’t actually related to deinterlining at all, but rather to the swap’s inconsistency. The new service pattern, with all of its benefits, will only be available on weekdays. This will regrettably add some additional complexity in riding the system, as the F will return to 63 St overnight and on weekends. This is the right tradeoff in the short term, as the M currently does not serve 6 Av or Queens Blvd on nights or weekends, and this small amount of complexity should not stand in the way of deinterlining. It does, however, make it much more valuable for the M to run its full route on weekends and later into the evening. This would not only double service on Queens Blvd, but would also give Brooklyn M riders more consistent service to Manhattan and Queens. We strongly encourage the MTA to look into extending the M on weekends and nights to fully lock in the benefits of the swap.

Nostrand Junction

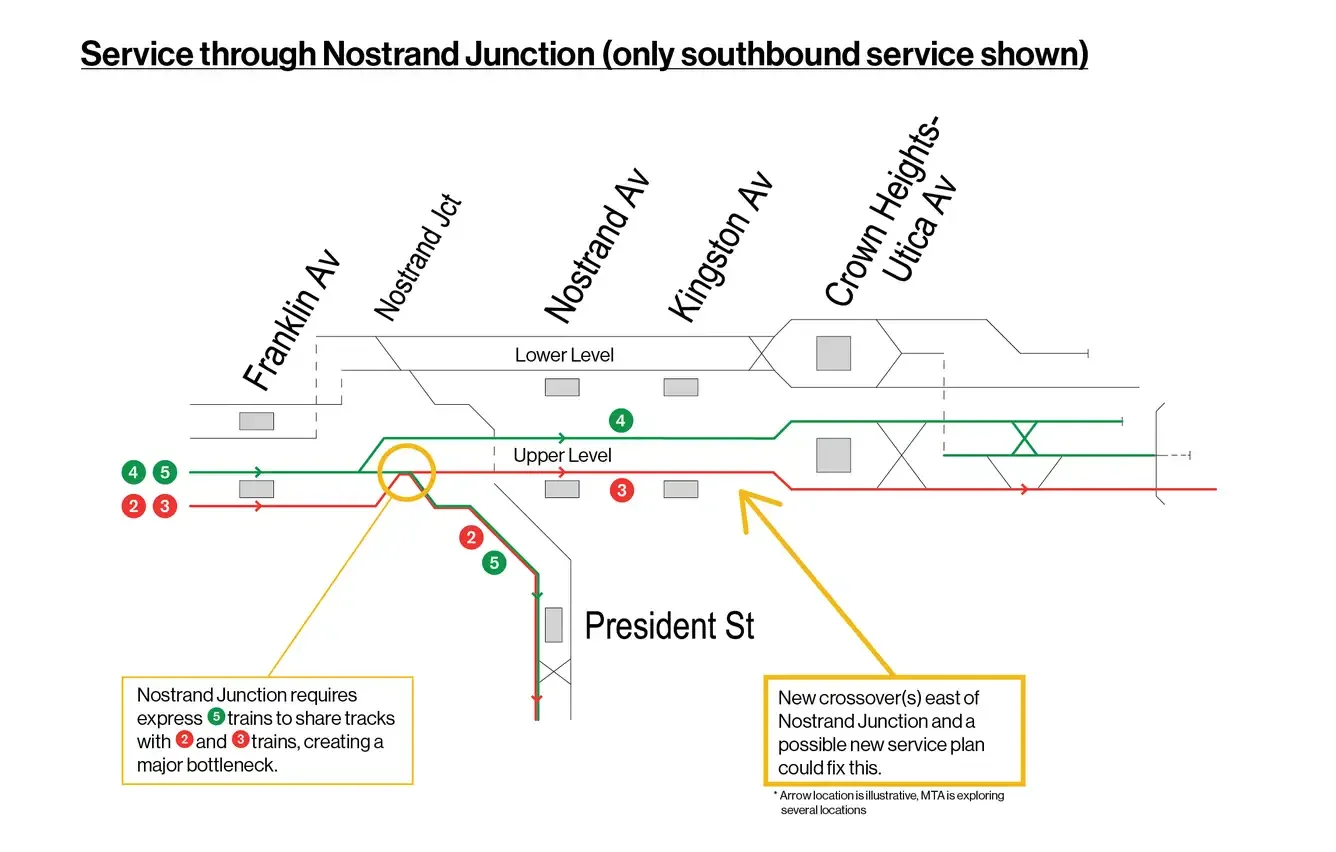

Nostrand (or Rogers) Junction is where the 2 and 5 join with the 3 and 4 on Eastern Pkwy in Brooklyn, immediately east of the Franklin Av station. Unfortunately, unlike the F/M swap, the junction was not built fully grade-separated, forcing the 2, 3, and 5 to all briefly share a single section of track. This imposes a significant capacity limit on the 2/3/5, limiting them to a combined 35 tph through the junction. As a result, the 2/3 are limited to 22 tph and the 5 to 13 tph, even though their Manhattan sections, the 7 Av and Lexington Av Expresses, are some of the most overcrowded lines entering Midtown. What’s more, because the 2 and 5 (and the 3 briefly) come together in a reverse branch, the junction is also the source of countless delays.

A track diagram of the current layout of Nostrand Junction with current southbound service highlighted.

Credit: MTA, via Gothamist

Solving this capacity bottleneck and perennial delay factory requires separating that shared section of track. This could be achieved by fully grade-separating Nostrand Junction like many other junctions across the system—a costly proposition—or it could be achieved by deinterlining the 2/3 from the 4/5, with the 2/3 both serving Nostrand and the 4/5 staying on Eastern Pkwy. However, in order to maintain service levels, deinterlining would require strategically adding new switches. In 2009, the MTA studied these options and found that full grade-separation would cost $1.6 billion, 4.6x as much as deinterlining with a new switch immediately east of the junction ($343 million). By 2023, the cost of deinterlining with upgraded terminal switches had risen to $410 million in the 20-Year Needs Assessment Comparative Evaluation, still far cheaper than the alternative. Then in 2025, the MTA included Nostrand deinterlining in the updated 2025-2029 Capital Plan, with a new switch immediately east of the junction. This plan (yet to be priced) would enable 4 and 5 trains to access the local track between Franklin Av and Utica Av. Otherwise, a new 8 train would be needed to serve those local stations, as planned in the 20-Year Needs Assessment; this would also maintain a less intensive reverse branch of the 5 and 8.

The benefits of deinterlining to remove this reverse branch of the 2 and 5 are massive. The MTA estimates that deinterlining Nostrand Junction will save riders 1.7 minutes every day, a cumulative 1 year of time daily [2] across over 300,000 daily riders. Moreover, in combination with planned signaling improvements (Communication-Based Train Control or CBTC) and switch replacements, this will allow both the 2/3 and 4/5 to run at 30 tph—a 36% and 15% capacity increase, respectively—greatly reducing crowding on 7th and Lexington Av. Some riders would have to transfer between the 2/3 and 4/5 at Franklin Av or Nevins St; that said, because the transfer would be a simple matter of crossing the platform, transferring riders will only incur an additional 1-minute penalty in return for far more frequent and reliable service.

Nostrand Junction deinterlining cannot happen immediately, as it requires the construction of the aforementioned new switches. Still, the MTA has now committed to deinterlining Nostrand by including these crossovers in the updated 2025-2029 Capital Plan. And while they haven’t yet committed to running increased service afterward, this project is part of an earlier service-led planning study of CBTC and capacity across the IRT (IRT Capacity Study), which presumed a future baseline of 30 tph on both trunks. The same terminal switches that are planned for deinterlining are also needed to improve the Brooklyn IRT terminals so that Flatbush Av, Utica Av, and New Lots Av can all turn 30 tph with CBTC. And given the extreme crowding on the Lexington Av Express and the study’s future baseline plan, it is very likely service will be increased once the 35 tph Nostrand bottleneck is removed, as recommended by the IRT Capacity Study.

The Holy Grail of Deinterlining: DeKalb Interlocking

Riders on the B/D/N/Q trains between Brooklyn and Manhattan are no strangers to delays. Trains often get stuck for minutes in the tunnel north of DeKalb Av station or on the Manhattan Bridge before entering the tunnel. Each of these services merges with at least two others, allowing delays to easily propagate and compound. Interactions between trains forced by interlining are so complex that forced waits are inevitable due to the impossibility of scheduling fully delay-free merges, even with recent MTA dispatching improvements. The impacts of this merge are so disruptive that DeKalb Interlocking is a top contender amongst advocates for the most disruptive case of interlining in the system. Combined with the truly ancient signals, this makes DeKalb the infamous delay capital of the subway.

The MTA plans to upgrade DeKalb Interlocking as part of the 6 Av CBTC project. This junction currently requires an employee at the station to push a physical button on a “model board” to select each train’s route. These controls are from the 1950s, and the buttons frequently break, making modernization a critical upgrade. Besides just the merge conflicts, CBTC will significantly speed up trains near DeKalb and on the bridge approaches, so it’s critical that CBTC is installed here as quickly and smoothly as possible. However, the current rolling stock complicates things. The old trains that will remain on the N/Q are not compatible with CBTC, and they will have to run alongside new CBTC-equipped trains through the interlocking before newer trains arrive to replace them. Thus, the MTA has asked for options in the RFI, outlining a few potential solutions.

One option is to convert the interlocking to CBTC, but retain all of the current wayside signals for the old trains and integrate them into CBTC. This has never been done before. For previous CBTC projects, the MTA kept a stripped-down version of the wayside signals for backup, but this has added enormous complexity and cost. For example, QBL East CBTC has been significantly delayed because there is barely anyone left who understands the ancient wayside signals. At DeKalb, it would be even worse, as the wayside signals would require full integration, not serving as a backup. The MTA has wisely transitioned to a “CBTC-Centric” approach for the recent Crosstown Line project, with far fewer wayside signals to reduce costs, and has committed to making all future CBTC projects CBTC-Centric. It would be a mistake to reverse course for DeKalb.

The second option would be to not install CBTC in the interlocking at all, and instead partially upgrade the signals with Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs). This would be an improvement—albeit nowhere near as much as CBTC—and it would have to be ripped out for CBTC shortly after, requiring lengthy shutdowns all over again.

But if the MTA deinterlines DeKalb, then CBTC can be added to 6 Av without any problem, as the B/D will be fully upgraded to new R211 trains by that time. This would greatly reduce the complexity, disruption, and cost of this signal upgrade, massively benefiting riders.

The drawbacks of deinterlining DeKalb Interlocking are somewhat stronger than the F/M swap or Nostrand Junction. Brooklyn riders losing a one-seat ride could only transfer at Atlantic Av, a notoriously long transfer; by riding the R one stop (only from 4 Av to Brighton); or at Herald Sq, already in Midtown. At face value, then, deinterlining DeKalb poses the potential for seriously inconveniencing riders.

This theoretical rationale for not deinterlining DeKalb, however, falls apart in practice. For one, few stations even benefit from one-seat rides. 11 express stations [3] see a choice between trunks in southern Brooklyn, but 29 local or branch stations do not. The increased convenience for riders at a minority of stations is paid for by increased delays and lower frequencies at all of them. Worse, the value of the added convenience of the one-seat rides created by deinterlining is very low. Every Broadway Express stop is less than a half-mile (10-minute) walk from a 6 Av Express stop; most stops are closer still. For most riders, then, a lack of choice between trunks has very little impact on their walking times in Manhattan. And both originating and transferring riders won’t have to gamble on which station to walk to in order to reach their destination sooner. Even for those losing one-seat rides, more reliable and frequent service will almost always overwhelm the downsides.

Given this cost-benefit analysis, we think the only reason DeKalb interlining has stuck around as long as it has is historical inertia. However, the existing pipeline of deinterlining projects, as well as the timing of signal and train upgrades, offers the opportunity to reconsider the status quo. We strongly urge the MTA to study the travel time savings for riders for different deinterlining schemes, assigning the B/D/N/Q trains to different lines in southern Brooklyn. We anticipate that riders plagued with historically unreliable service will see faster and significantly less stressful rides to boot. It’s rare that bringing improvements of this magnitude to riders can be cost-effective or even save money. We hope the MTA seizes the opportunity.

Simplicity is Reliability and Speed

The New York City Subway is the most complex in the world, with a huge number of lines merging with one another, often multiple times over the course of their run. This historical artifact of the system's creation is almost unique in the world, and causes issues that often don't arise elsewhere. At worst, the subway can be a house of cards, where a single issue on one train can cascade and cause delays across the entire city.

When it comes to train routing, simplicity is better. It makes scheduling far simpler, it eliminates conflicts between trains, it removes switches, allowing service to run faster and more frequently, and it makes the entire system more reliable. Simplifying the subway revolves around deinterlining. It may seem counterintuitive at first to riders who lose a one-seat ride, but all riders are sure to notice a more reliable, faster, more frequent subway network.

We celebrate the MTA for finally taking to steps to deinterline some of its biggest bottlenecks, and encourage the MTA to continue the process. It is one of the easiest, most cost-effective ways to build a subway system that works better for everyone.

Corrections

An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that the MTA's new schedule for the M train did not increase service. The schedule does include a modest service increase, just not one that reaches the levels promised.

Footnotes

47,000 AM riders * 2 * 1 min saved/rider = 65.3 days per rush hour

319,900 daily riders * 1.7 min = 378 rider-days per day

4 on 4 Av and its branches (36 St, 59 St, New Utrecht Av-62 St, Coney Island-Stillwell Av) and 7 on Brighton (7 Av, Prospect Park, Church Av, Newkirk Av, Kings Hwy, Sheepshead Bay, Brighton Beach). Coney Island is not counted as it will always retain one-seat rides to both Manhattan trunks no matter what deinterlining plan is used.

Acknowledgements

ETA would like to thank the following for contributing to this statement:

John Ericson

Madison Feinberg

Robert Hale

Darius Jankauskas

Blair Lorenzo

William Meehan

Samuel Santaella

Khyber Sen