Public Comment on the IBX SEQRA Draft Scoping

This statement was submitted to the MTA as a public comment on the Interborough Express (IBX) SEQRA Draft Scoping Document. Public comment closed on November 26, 2025.

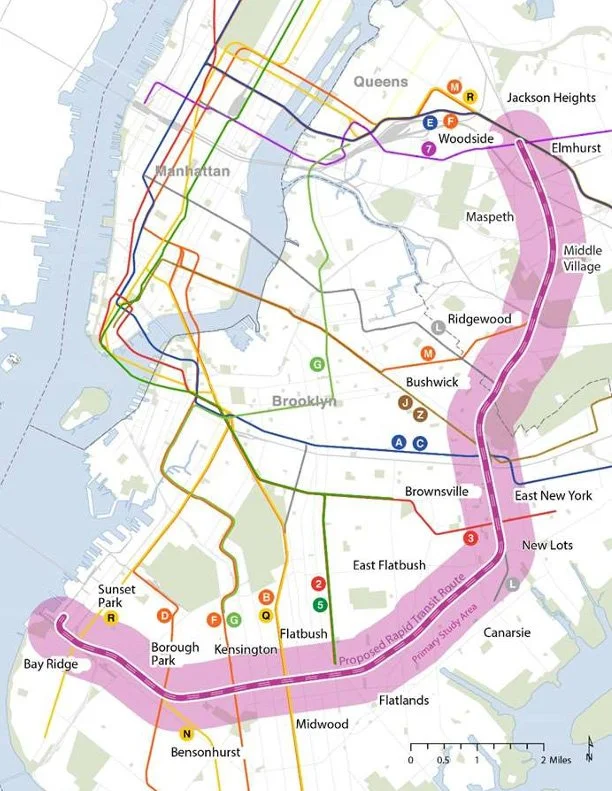

The route of the Interborough Express and its project area (Map source: MTA Draft Scoping Document)

The Effective Transit Alliance (ETA) supports the Interborough Express plan and the transformative improvements it will bring to Brooklyn-Queens connectivity. This includes the route and planned station locations. However, the publicly available plans for the project contain gaps in provisions for high-quality service and future capital improvements to the system. We raise these concerns so they receive further analysis during the scoping process. We specifically highlight deficiencies in previous analysis of automated systems in the design process, and the risks this poses for adequately serving demand. Additionally, we suggest studying in-system connections, especially at high-ridership transfer stations. Finally, we also suggest designing provisions for future system expansion.

It’s especially important to provision for very high frequency to support the planned capacity. The MTA’s ridership analysis in the PEL study found an anticipated peak ridership of 1,287 riders per 15 minutes at Brooklyn College. However, the MTA’s current planned headways and previously specified vehicle capacity (390) would be insufficient to serve currently projected demand (which has since risen 35%). This situation will only grow worse with new development near the stations as a result of City of Yes and potential future upzoning, while higher frequencies will only drive ridership even higher. To ensure sufficient future capacity, we recommend roomier high-floor, open-gangway vehicles and a design for 90-second headways. At these headways, the currently provisioned train length of 325 ft is sufficient, and further cost may be saved by initially shortening the trains while retaining the provisions for longer ones matching the length of the platforms. The MTA should design the system to support these frequencies now, covering signaling, yard space, terminal design, traction power, and substation provisions, to futureproof it for future generations.

In particular, committing to high-floor vehicles is crucial. Low-floor vehicles have much less room, as space is taken up by wheels and electrical equipment, reducing capacity and slowing passenger flow within the railcar. More importantly, they are fundamentally more complex, which results in higher capital costs per car and more costly maintenance as trains break down far quicker. This leads to needing a much larger spare factor, increasing fleet size and cost and necessitating a much larger yard, which will very likely outweigh the cost of building high platforms. For example, in Boston, the partially low-floor Green Line has a spare factor of 64%, while the high-floor Red Line is only 18%, more in line with NYCT’s 17.5% target. Moreover, building platform screen doors on low-level platforms is uncommon and will increase the cost and complexity of doing so. Most light metros worldwide use high-floor trains for this reason, so there’s also a larger market for such rolling stock, and there is less risk than trying to attempt the uncommon low-floor light metro.

The MTA justified light rail as the preferred mode for IBX in part on the grounds that it would see peak headways of 5 minutes, whereas automated guideway transit would only see 8-minute headways. This mischaracterizes automated systems around the world: the technology is routinely capable of 2- and even 1.5-minute headways, using CBTC just like the IBX is likely to use. It’s increasingly common on new subways designed for intermediate capacity, combining small stations to reduce construction costs and very high frequency to maintain capacity. Examples include REM in Montreal, the Singapore Circle Line, the Vancouver SkyTrain, the Copenhagen Metro, and all new metro lines in Italy, ranging from 130 to 230 ft long trains. Multiple vendors are available for the systems and the rolling stock.

Automation significantly reduces marginal operating costs, with WMATA estimating 41%, affordably allowing high-frequency off-peak. It enables very high peak frequencies with much higher reliability, and this reliability of operating behavior means even faster speeds (WMATA estimates 7% from automation alone, while Paris observed 23% with automation and CBTC on Line 1), faster turnaround times, and less energy usage. These can all combine to reduce how many trains are needed, cutting rolling stock and yard capital costs. And finally, platform screen doors ensure the highest degree of safety. Thus, the MTA should automate the IBX.

We also suggest increasing planned off-peak service. IBX relies on transfers to radial lines, including two- and even three-seat rides. Passengers would only be riding IBX for a portion of its length, and would spend a significant share of their trip waiting for a train. Mode choice models find that passengers consider a minute spent waiting to be as bad as about 2 minutes spent on a moving train. At rush hour, very high frequency is important for capacity, but off-peak, a system capable of running every 3–4 minutes affordably is important for passenger convenience.

To further improve the IBX’s transfers, in addition to increasing IBX frequency, the MTA should design more in-system transfers rather than settling for out-of-system ones. We respect the MTA’s desire to reduce costs on the project, but this decision may not be cost-efficient for some critical transfer stations. The same ridership models that estimate the waiting penalty is a factor of 2 also estimate the same penalty for transferring between platforms. For very close stations, like 8 Av or Wilson Av, in-system transfers are cheap and should absolutely be built. For stations that will see high transfer volumes but longer transfer distances in today’s plans (e.g. Flatbush Av-Brooklyn College, Broadway Junction, and especially Jackson Hts-Roosevelt Ave), we suspect additional investments in facilitating in-system transfers (such as pedestrian tunnels) may unlock higher ridership and decrease project cost per rider. We also believe transfer infrastructure may prove worthwhile across the corridor in the future, if not today. We suggest designing each applicable station with provisions to construct such infrastructure. This may be as simple as leaving sufficient space for an elevator, elevated walkway, or tunnel portal, potentially saving hundreds of millions of dollars in future work.

Finally, the IBX may grow future demand for cross-borough connectivity in the future. This could include demand for service to the Bronx, LaGuardia, or Harlem. We would encourage provisions for northward expansion in the form of tail tracks to enable future system growth.

We hope that these points are included in project scoping to design a system that best serves riders both from day one of operations and for generations to come.

Acknowledgements

ETA wishes to thank the following members who contributed to this public comment:

Madison Feinberg

Darius Jankauskas

Alon Levy

Blair Lorenzo

Vinay Madhugiri

William Meehan

Khyber Sen